How to Safely Fell a Tree

Tree Cutting: Simple Practices to build your soul

Words & Images by Blaine Eldredge

“There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm. One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery, and the other that heat comes from the furnace.”

Aldo’s right, though there’s a certain philosophical heavy-handedness to the concept as such. In practice, it’s quite fun. If you want to nourish your soul, adopt simple, real practices and do them. I love cutting firewood. The tools are straightforward and the motions are simple. Most guys can split a block without hurting themselves. And there’s still plenty to know because, like learning to kiss or throw a punch, you’ve got to get the basics down or you’ll get yourself in trouble.

The Basics of felling a tree

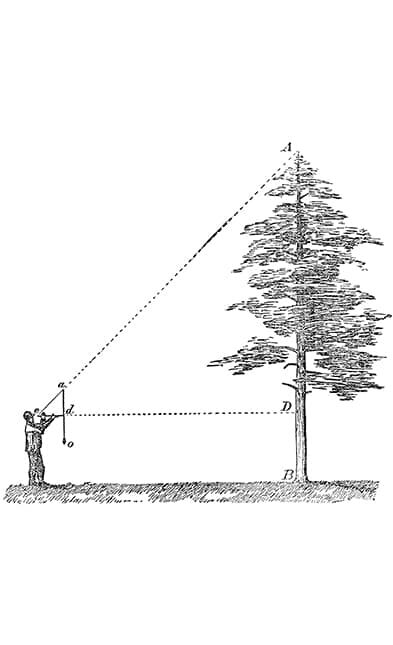

1.Determine the height of the Tree

Here’s one cool trick—you can determine the height of a tree with a stick the length of your arm. I mean it. It works this way: pick up said stick. Hold it at a 90-degree angle to your (straight) arm. Then, point your arm at the base of the tree. Don’t change the angle of the stick. Move backward or forward until the top of the stick lines up with the top of the tree, and you’ve made a right triangle. The tree is as tall as the distance between its base and your shoulder.

2. Cutting a Hinge

When you cut a hinge to fell a tree, it should be 10 percent of the DBH, or the Diameter at Breast Height, 4.5 feet off the ground. If the tree has a 30-inch diameter, you need a 3-inch notch to fell the thing right.

3. Determine an Escape Route

Before you fell a tree, you determine an escape route. You need to get 15 feet away from the tree at a 45-degree angle to the face of your hinge. Doing so will get you out of the way of most of the hazards, most of the time.

But that’s the science. The experience is the gold—the showers of sawdust. The tang of 50:1 fuel. The rough sensation of a wood block on your shoulder. I love stacking, splitting, and burning wood. After long days in front of a computer, I’ll split a few blocks and build a fire, even if I don’t plan to sit in front of it. The feeling, the reality, the immersion in it, relieves me. There’s nothing like swinging an axe to situate yourself in an ageless procession of men.

But it doesn’t have to be firewood. A buddy of mine bakes bread. The ingredients are simple: flour, salt, oil, yeast, water. And yet. There’s a world of inscrutable science. The temperature of the water. The life of the yeast. The feeling, which has to be experienced, not communicated, of perfectly-kneaded dough. It anchors him in the real world. It forms a place in his soul suited to life with God.

“Find something simple, something you like, and then rig your life to fail without it. ”

For another guy, my neighbor, it’s working on his car. I’ve learned to love the smell of brake cleaner by proximity. For my brother Sam, it’s tuning his bike. For Luke, it’s making dynamite paleo stews. The point is, reality is your friend. Simple practices that connect you with the real world build your soul, and you don’t have to put in additional effort. It just happens.

This is good news because most of us set the bar too high. Camping trips, long trail runs, days fishing a river. But really—you can real-ify your life without much additional effort. Find something simple, something you like, and then rig your life to fail without it. Get a wooden box coffee grinder and throw out your electric one. Volunteer to bring homemade bread to that weekly dinner. Buy an old dirt bike and set a weekly time to wrench on it with a buddy.

Or, like me, get a wood stove and learn to love being around it. Your soul will thank you.

Print isn’t dead.

If you enjoyed this article, you’d probably love more like it in the And Sons print issue. If you don’t have one of these on your coffee table right now, you should probably go explore our back issue catalog.